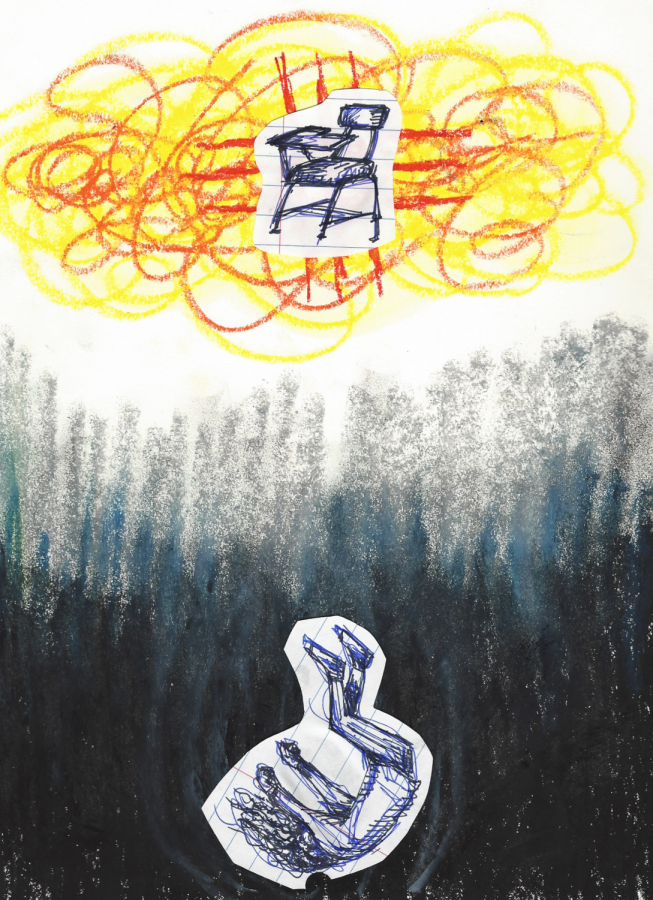

The Internalized Divide

AP classes are divisive and exclusionary.

Ask yourself: what is your classroom really like? Is it a welcoming environment that encourages peer support and vulnerability? Or is it full of judgment and hostility towards making mistakes? For students in Advanced Placement classes, the latter is often true.

“In an AP class, the culture isn’t just to do well but to outcompete,” said Mr. NK, who teaches AP Human Geography and AP Project Based Government.

While not all AP classes are hostile, with heavy workloads, AP environments tend to be contentious. This contention creates pressure on the students to have high performance goals.

“For students in Honors and AP classes, I commonly see a lot of anxiety and pressure to perform at a high level,” said Garfield counselor, Mr. Lee.

A majority of the students who take the majority of Advanced Placement courses have been a part of a Highly Capable Cohort (HCC) in middle and elementary school.

Getting into HCC programs depends on environmental factors, like parental influence and socioeconomic status, rather than just individual choice. Students can be tested multiple times if their parents have the money to pay.

“The first time I took the test, I didn’t make it in, and they had to pay for a second test for me to get into the program, ” said senior Tate Linden. “Which a lot of families wouldn’t be able to afford in terms of time and money.”

This socioeconomic divide has turned into a racial divide, leaving general education classes majority Black and Latino while HCC classes are majority white and East Asian.

In 2018-2019, 58% of the HCC program was white while only 1% of the HCC program was Black.

This racial divide has historically carried over into Garfield’s AP classes, but even as these classes become more desegregated, there continues to be exclusivity in the classroom.

“A lot of our African American and Latino students feel that maybe they’re not acknowledged as much in those classes,” Lee said, “I’ve had a lot of students say that their classmates aren’t welcoming of them and that they feel ostracized in the classroom.”

HCC students have grown up learning in an environment with a lack of diversity among learning styles and abilities. These students bring classroom expectations and learning ideals into their AP and honors classes.

“With any type of Honors system, I think there’s this expectation that everyone has passed a certain point and is already at a specific level already.” said senior Emily Wills.

Like Emily, I assumed that I was the only one in my Honors classes that was falling behind. I am not from an HCC background, and while taking Honors Algebra 2 Freshman year, I felt completely out of place. I was a focused student in middle school but this was a rude awakening for me when coming to Garfield. I had to come up with my own definition of success because taking AP classes and getting a 4.0 didn’t give me fulfillment.

Many HCC students never reach a point of satisfaction in their education, mostly a result of their early HCC schooling. High pressure, education-focused parents put their kids in HCC classes, teaching kids that learning is about getting ahead.

“It seems like students have internalized this pressure to be successful and to achieve… They don’t know a different way.” Neufeld-Kaiser said.

Young kids are taught that to have a good education, they need to be in high level and honors classes.

“The social dynamic was really competitive at times,” Linden said. “A lot of people in HCC classes, even in early elementary school, looked down on people in general education classes.”

Students in HCC are trained to constantly prove themselves, specifically over their classmates to demonstrate they’re “gifted” and not at the level of the kids in non-HCC classes.

“When we start by segregating our classes by race, and then we tell everybody in AP classes that they need to be relentlessly achievement oriented to always be better than everybody else, it doesn’t just make the kids competitive in their class,” Neufeld-Kaiser said. “It also is exacerbating the racism.”

While internalized racism does create a social divide among the “gifted” and “non-gifted” students, the root of the issue lies in how we think about education.

We can’t push students into high level classes without expecting consequence. Instead, we need to work to create learning environments where full integration can happen.

“Society has this expectation that you have to perform at a peak level, all the time, in AP classes, and I don’t subscribe to that,” Lee said.

AP courses move at grueling paces, but combined with a lack of social acceptance and peer support, kids who didn’t grow up in gifted programs face more disadvantages.

De-tracking AP classes, which means AP classes for all, is a step in the process of desegregating our classrooms, but the issues are much deeper. Let’s work on our classrooms, opening up to vulnerability and asking “stupid” questions.

Learning to collaborate with our classmates, instead of beating them in an endless game, will create a better space for everyone to succeed.

Izzy Lamola is a senior writer on The Garfield Messenger. They love InDesign, despite the tedious work, and is a lover of opinion pieces and op-eds. They...