A Brief History of AAVE

The origins of African American Vernacular English

(Mis)Understanding AAVE

On December 18, 1996, the Oakland Unified School District passed a resolution for public schools to use AAVE as a tool in teaching standard English and to provide resources to help educators understand AAVE. This sparked national outrage. The backlash levied at the resolution mirrors incorrect and racist ideas about AAVE still maintained two decades later: that AAVE is “lazy,” “broken,” and “worse” than standard English. The reality is that AAVE is just as sophisticated as standard English and deploys many distinctions and nuances standard English lacks. Despite this, misconceptions about AAVE abound and have major consequences for AAVE speakers who have to face racially-motivated attacks and implicit bias for using it.

This article aims to present an introduction to the history of AAVE, some of its basic grammatical distinctions from standard English, and the impact of misconceptions about AAVE. This is hardly exhaustive and AAVE isn’t a monolith; different regions have their own nuances and this article only covers some basic traits found in most varieties of AAVE. Additionally, neither of the authors are fluent in AAVE, and as such we’ve attached citations to make sure our commentary is accurate and to provide more detailed readings for those interested in AAVE linguistics.

The exact origins of AAVE are still hotly debated by linguists, who fall into two camps. The first camp supports the dialect hypothesis, which proposes that the earliest forms of AAVE emerged from African slaves coming in contact with indentured servants and learning their dialect in order to communicate with the servants and each other. Over time, this dialect evolved into AAVE.

However, the Creole hypothesis proposes that AAVE began by mixing various West African languages with English to create a new means to communicate, and that over time this creole converged with standard English. Creolization is a common process that results from lots of people who speak different languages needing a common means to communicate and mixing their languages together to make one. Most regions with large slave plantations developed creoles since West Africa has hundreds of unique languages and cultures which European slave owners forced onto shared plantations. The term creole itself is drawn from Haitian Creole, which emerged as a direct result of the slave trade.

Creoles generally aren’t mutually intelligible with any of the languages they draw from. For example, Gullah, a South Carolinan creole that primarily draws on English, is completely unintelligible to most English speakers

Regardless of which hypothesis you find more convincing, we know this older form of AAVE emerged in the South since slavery concentrated most African Americans on southern plantations. As a result, AAVE includes many features of southern pronunciation and grammar, like the word ain’t.

AAVE spread across the country with the movement of Black people. The largest movement, deemed the Great Migration, took place in the early 20th century when millions of Black folk moved to all corners of the country, fleeing Jim Crow and the KKK in search of opportunities for a better life.

As AAVE spread across the United States each region developed distinct differences just like standard English dialects: AAVE in Baltimore differs from its counterparts in Los Angeles or New York, and the largest distinctions are perhaps between rural and urban varieties of AAVE.

This spread has also influenced standard English. Many phrases, like “to have a beef with” or “give props” are commonly used in standard English without speakers realizing their origin in AAVE. The internet has only accelerated this process. Slang spreads quickly across social media or through music and memes. Modern slang like “bae,” “squad,” or “yas queen” aren’t often attributed to AAVE and many speech patterns that are commonplace among younger generations are borrowed directly from AAVE, like plopping as* after an adjective for emphasis.

Understanding AAVE

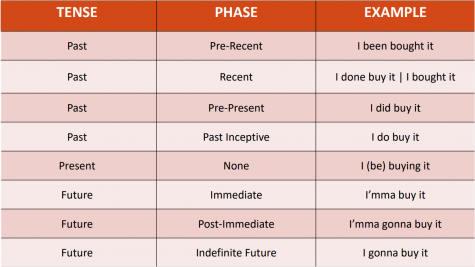

A complete introduction to AAVE grammar is out of the scope of this article, but the most distinctive and worse understood difference between AAVE and standard English is AAVE’s nuanced tense system. Since non-AAVE speakers don’t understand this system it’s often viewed as “random” or “broken” despite communicating highly precise information. Beyond the three tenses of standard English: past, present, and future, AAVE breaks each tense into several phases. For example, “I’mma buy it” indicates one is about to buy something, while “I gonna buy it” indicates one will buy it at some undefined future time.

Basic construction of AAVE phases, although these forms vary depending on the dialect – the least intuitive in standard English, but perhaps familiar to Latin learners, may be the past inceptive, which spans from the immediate past to the near future.

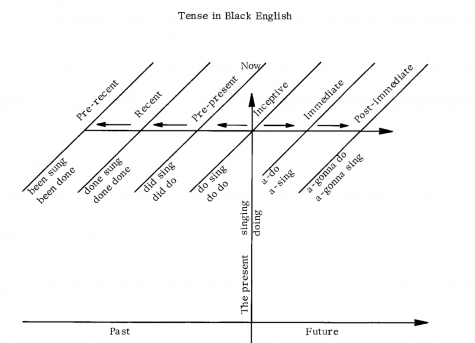

Graphic from Joan G. Fickett’s “Tense and Aspect in Black English”. Note that a- indicates the “I’mma” in the first chart.

In addition to the phase system, AAVE has three especially important aspect modifiers: be, stressed been, and done. Aspect modifiers are words that change how we understand the way an action spans through time. For example, in standard English the suffix -ing changes the aspect by indicating an ongoing action. In AAVE, be indicates a habitual action, so while “I workin’” might indicate that one is at work presently, “I be workin’” would indicate that somebody has been doing work for a while, although not necessarily at this very moment. Stressed been is similar to habitual be, and indicates a longer-term action that isn’t necessarily habitual, so “I been workin’” would indicate one has been working for a long time and still is. Done, by contrast, indicates that an action is complete, so “You done bought it” creates a sense of finality.

Understanding Matters

Despite AAVE’s systematic and complex structure, it’s still highly stigmatized as a result of rampant racism and classism. Studies have verified AAVE is viewed as less intelligent, even among Black communities, forcing AAVE speakers to code-switch and watch their speech in educational or white-dominated settings. This has an especially pronounced effect in court, where one study found transcriptions of AAVE were wrong two-fifths of the time–sometimes reading the exact opposite of the testimony given–and that white judges and juries misunderstood testimony given in AAVE. In the George Zimmerman case overshooting Trayvon Martin, one important witness, Jeantel, spoke in AAVE. The judge and even a juror frequently asked her to repeat herself while the stenographer got many statements completely wrong, confusing “I could” and “It was Trayvon” for “I couldn’t know Trayvon” and “I couldn’t hear Trayvon.” Online discourse labeled Jeantel’s story as incoherent and incomprehensible. At one point Jeantel said “I was been paying attention, sir,” with the stressed been–this indicated she had been paying attention for a long while, but instead of demonstrating her credibility as a witness, the stressed been just confused the jury. Zimmerman was eventually acquitted for shooting Trayvon, in part due to the inability for the White jury to understand Jeantel’s testimony.

This brings us back to Oakland. In 2007 the Linguistics Society of America released a statement in defense of the School District’s policy, reading:

The systematic and expressive nature of the grammar and pronunciation patterns of the African American vernacular has been established by numerous scientific studies over the past thirty years. Characterizations of [AAVE] as “slang,” “mutant,” “lazy,” “defective,” “ungrammatical,” or “broken English” are incorrect and demeaning… the Oakland School Board’s decision to recognize the vernacular of African American students in teaching them Standard English is linguistically and pedagogically sound.

Many of the policy’s original critics, like civil rights leader and Reverend Jesse Jackson, were eventually won over to the cause by a flurry of interviews and op-eds written by linguists in defense of Oakland’s policy. The statement was ten years overdue, but also a good sign: it shows us that education works and that by educating communities it’s possible to break down the stigma that surrounds AAVE and fight back against linguistic racism.

Citations

Fickett, J. G. 1972. “Tense and Aspect in Black English.” Journal of English Linguistics Linguistics, 6(1), 17-19. doi:10.1177/007542427200600102.

Marguerite, R. 2014. “Stanford linguist says prejudice toward African American dialect can result in unfair rulings.” Stanford News. https://news.stanford.edu/news/2014/december/vernacular-trial-testimony-120214.html

Moore, T. 2016. “Dialects Accents and Intelligence: A Study on Dialectal Perceptions.” Undergraduate Research Posters at Cleveland State University, 22.Russo, A. 2018. “Lessons from the media’s coverage of the 1996 Ebonics controversy.” Phi Delta Kappan. https://kappanonline.org/russo-ebonics-coverage-65649-2/

Wolfram, W. 2004. Edited by Bernd Kortmann and Edgar Schneider. “The Grammar of Urban African American Vernacular English.” The Handbook of Varieties of English.

Anonymous • Jul 22, 2024 at 10:10 AM

this reads like an Onion article

no • Jan 4, 2024 at 11:29 AM

does anyone actually read this???

adviser • Jun 21, 2024 at 1:43 PM

Thousands.

Ana • Nov 6, 2022 at 5:16 PM

Does anyone know who wrote this article, I cannot find an authors name anywhere and its somewhat frustrating.

Krystal Rodriguez • May 9, 2021 at 3:21 PM

Ever since I’ve been more active on social media I realized how much AAVE I’ve used without conscience. I always wanted to learn more about the different things black and African Americans have to struggle with living in a white dominate opinion society. Thank you so much for this info. I really enjoyed reading this article and learning more about the language.

George • Jun 22, 2022 at 9:35 AM

It’s not a real language. It’s poor English

Florence • Dec 4, 2024 at 5:53 PM

George, if they can communicate and express themselves with others, then it is a language.