Historical Architecture In The Central District

A deep dive into Architecturally and historically significant buildings in the Central District.

Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute on left, Washington Hall on right.

Historic architectural landmarks throughout the Central District offer a memento from the past. The details, big and small, in the architecture are full of stories and history.

These structures have been home to many different ethnic groups in the Central District over the years, including Jewish, Japanese and African American populations.

“From 1890 until World War I, the Central Area was a predominantly Jewish neighborhood… After World War II, the Central Area became home to most of Seattle’s growing Black population because of housing discrimination and restrictive covenants,” wrote Mary T. Henry for Historylink.org.

Most of the older and architecturally significant buildings in the Central District have been used for many different purposes over the years.

In this neighborhood, “African Americans primarily use buildings left by previous occupants of a community. It’s why so many of our institutions and some churches are in former synagogues,” said Donald King, a licensed architect for over 40 years and a long time resident of the Central District.

The Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute is a prominent example of this re-purposing. The building was a synagogue before it was sold to the city in 1972, and put to use as an arts institute serving mainly the Central District’s African American community. The institute hosts anything from film festivals, to spoken word and theater performances.

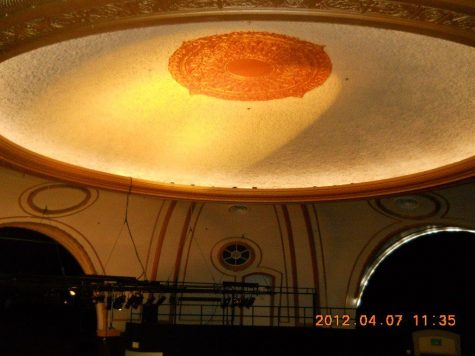

Built in 1915 and designed by B. Marcus Pritica, the structure has a unique look as it was designed to be a synagogue. From a distance the building’s prominent dome stretching up from the detailed patchwork on the walls can be seen. Despite it’s historical elements, changes to the architecture had to be made after the city took over the building.

“Unfortunately when the city bought the building they had to remove any religious symbols,” said Sandra Boas-DuPree, operations manager at the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute. On the main entrance of the theater, a book that used to have the ten commandments written on it had to be scraped clear. Inside the building, though, intricate parts of the dome have still been preserved.

“They did not remove the star of David, there’s a bunch of them on the ornate portions of the dome that come down and you can walk right up them and see,” Boas-DuPree said. Another prominent piece of the interior that was preserved, were two original Tiffany lamps in the lobby, estimated to be almost a hundred years old.

Image by Sandra Boas-DuPree

Domes are a traditional part of architecture in synagogues, and this design was intended to allow the best movement of sound. “It has to be related to the way the services are conducted with the singing. And that’s the biggest and most important aspect of this building: that we’re sharing culture with the Jewish faith,” Boas-DuPree said.

The architecture lends itself to the viewing experience as well. “Just the feeling you get from it when you walk into the theater and you’re under a dome, I think for the audience it makes it special and it makes it more of a pleasure to sit in theater,” Boas-DuPree said

Image by Sandra Boas-DuPree

Washington Hall is another architecturally significant landmark in the Central District. Built in 1908 by the Danish Brotherhood, this building has served as a space for primarily African American audiences and performers. The unique half circle windows and early 20th century brick stands out against the array of modern townhouses that surround it, and is one of the few old performance halls in the city along with the Broadway Performance Hall.

“The public ‘dancing hall’ now known as The Ballroom, is one of the largest still standing buildings in the city with spring loaded dance floors, horseshoe balcony, and proscenium stage,” said King Khazm, director at the Washington Hall and Co-Director of 206 Zulu (a community based organization located at the Washington Hall). The distinctive aspects included in the architecture show how the building served community members.

“Public spaces were noted by the arched windows on the exterior and private spaces by square windows. The Danish Brotherhood Lodge 29 also provided 2nd and 3rd floor single room occupancy units (also known as boarding units) on the back west side of the building for their members and newly arrived Danish immigrants,” said Kitty Wu, another Co-Director at 206 Zulu and manager of the rental program at Washington Hall.

Image by Julia Wartman

The structure is still very similar to what it was in the early 1900s, and remains a symbol of the Central District’s flourishing arts and entertainment scene, both past and present.

“From the start, the stage at Washington Hall has been in constant demand, hosting Danish and Yiddish theatrical productions in the 1910s, Filipino Youth Club dances in the 1930s, and even boxing matches in the 1950s. In the 1970s, the Hall became the official home to On the Boards, a non-profit arts organization that would stage contemporary works for the next 20 years. Local theater companies, like Nu Black Arts West Theatre, continue to stage original works at the Hall,” King Khazm said.

The historic architecture of the Central District can also be seen on residential streets, as many of these homes were built in the early 1900s.

“There are periods in 20th century American architecture that there was not a lot of construction done, like during the Great Depression of the 30s and during the war years,” King said. “So what you can find in some of the oldest homes in the Central District, are homes built between the late 19th century and the late 1920s.”

The ‘Yesler houses’ and ‘23rd Avenue House Group’ are both historically landmarked homes. But there are also many houses not landmarked by the city that hold historical significance in the community. These older homes can often be identified by peaked roofs, detailed porches, or masonry work on the structures.

“These are valuable homes now. They have a charm that people look for,” King said.

Keeping up these old buildings is not an easy task though, and oftentimes there is push back from consultants or owners of the property.

“People feel forced to use an existing building when they would just like the new shiny building,” King said. “Even though the building might have historic value and landmark status, some people feel that they are burdened by that.”

There are many challenges that come with the process of upkeep and renovation to an old building: earthquake retrofitting, replacing decaying material, and updating plumbing and electricity.

Knowing not only the struggles that come with restoring an old building, but also keeping it intact during rapid gentrification, gives perspective on why these architectural landmarks in the Central District are so important to the community, and demonstrates why they should be appreciated.

“There’ve been struggles to keep us here, and to keep us here as the way we are to honor African American arts and community,” Boas-DuPree said.

“[These historical buildings] were saved or created for the Central District of the African American population, but they have become more significant and valuable to continue to save because of the displacement,” King said.

Anne Podney • Dec 11, 2020 at 5:36 PM

This is a really interesting article and I can’t wait for the chance to go inside the Hughes Center to see the beautiful interior. It is fascinating also to find out how many different ethnic groups have used these buildings. Nice job, Julia!