On Impact

Concussions in youth and high school sports.

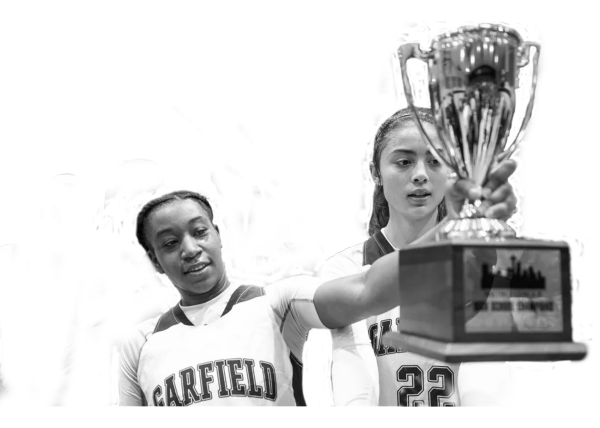

Everything seemed to be going normally for Garfield junior Malini Williams during an April soccer game earlier this year. The sun was out but the air stung, a typical spring day in Seattle. As always she provided a watchful eye from her goalkeeper position, scanning the field routinely to make sure her defenders were in place to counter any sudden runs from the opposing offense. Then she got kicked in the head.

“I got a throbbing headache and my head felt really fuzzy, like it was full of cobwebs,” Williams said. “I kept trying to shake my head a bunch to clear it up but that just made it worse.”

For Williams, this was the second of three concussions she has fallen victim to since 2013 and the first of two concussions suffered between April and September of this year. This is a worrying trend. She says that after three concussions in one year, her parents will not allow her to return to the sport. Williams has had two in five months.

“I’ve definitely lost a lot of my aggression and confidence as a result of the concussions because I’m just worried I’ll get another one,” Williams said. “Yet I don’t want to quit. I want to keep playing because it’s a part of soccer.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a concussion as a type of traumatic brain injury induced by a sudden hit that causes the head and brain to move back and forth rapidly, sometimes leading the brain to “bounce around or twist in the skull.” According to the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, they account for 12% of the 1.35 million sports related trips to the ER among those under 18 in the US.

The Seattle Sports Concussion Program is the leading group on tackling concussions in youth and high sports. An alliance between Seattle Children’s Hospital, Harborview Medical Center, and UW Medicine, the program is dedicated to providing “the right treatments at the right time to keep your young athlete safe and healthy as they recover from their injury.”

Andrew Little is the manager of athletic trainers at Seattle Children’s Hospital. He believes that it is important to recognize and be careful with concussions but also to not allow them to negate participation in sports or exercise.

“While it is impossible to eliminate all concussions in sports, concussion prevention strategies can reduce the number and severity of concussions in many sports; though there isn’t a lot of supporting evidence that this is attributed to individual injury-prevention strategies,” Little said. “There is different risks in all forms of sports, and navigating that risk can be a complex decision, but it should not eliminate participation in regular physical activity. There is a sport or activity for everyone, we just have to find what that specific thing is.”

Recently, the discussion on concussions and their prevalence in contact sports, football in particular, has exploded on the national stage. The majority of these conversations center on chronic traumatic encephalopathy, commonly referred to as CTE, a type brain disease in the realm of dementia that Boston University’s Dr. Ann Mckee says is associated with “aggressiveness, explosiveness, impulsivity, depression, memory loss and other cognitive changes.”

CTE has made headlines this summer when a study from Boston University published in July revealed that CTE was present in 177 out of 202 brains examined from deceased football players across all levels, including 110 out of 111 brains specifically from the NFL level.

A prevalent issue with the diagnosis and treatment of concussions for athletes is a failure to self report the symptoms of head trauma. Whether from a developed stigma that coming out of competition for a concussion is a sign of weakness or simply a raw desire in athletes to continue competing for the love of their sport, the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago reported in 2012 that 42% of athletes intentionally do not report their concussion symptoms.

This failure to report is not unique to any level of athletics. In a Thursday Night Football game against the Arizona Cardinals earlier this NFL season Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson was forced out of the game after the officials suspected he had concussion like symptoms. NFL policy requires him to be examined by medical professionals before returning to competition. Instead, Wilson was shown going to the tent where he should have been examined, but stayed there for a split second before running back onto to the field. He took the next snap without any medical examination.

Malini Williams did more or less the same thing last spring.

“Initially I said to my teammates and the ref that I was okay, I was lying, and they were okay with that,” Williams said. “I played for another 20 minutes until my teammates noticed that I wasn’t really functioning properly and I got subbed off and didn’t play the rest of the game.”

Unfortunately, Williams had a game the next day. These games came directly after a five month stretch in which she had been sidelined with a broken femur, all the while yearning to get back on the field.

“The next morning I woke up with a massive headache, but I lied to my parents and my coach and said I was okay to play,” Williams said. “I didn’t want to sit out anymore because it is so frustrating [to just watch]. I took some Advil and played that game. Afterwards I could hardly stand up straight because I was so dizzy.”

Garfield athletic trainer Carmay Jones-Isaac believes that it is essential to create an environment that makes student athletes feel safe and willing to report concussions.

“It would help if students could show empathy towards one another and treat the injured athlete with compassion,” Jones-Isaac said. “Concussions can be an invisible injury… We have to be aware of how much the interactions the injured athlete has with teammates, coaches and even teachers influence the healing process. This is especially true since concussions can lead to the development of depression in some athletes due to the invisible nature of the injury, a lack of support, an athlete’s loss of their place on the team or an unknown timeline for their recovery.”

Williams is in complete agreement she offers some key advice for those with friends or family members suffering from a concussion.

“The most important thing for student athletes suffering from a concussion is people who are there for emotional support,” Williams said. “Concussions can be extremely frustrating and take time to heal, and sometimes that’s longer than you think it should be taking.”