Who Told You to Go That Hard?

The bleacher banisters are bracing themselves against the pulsing crowd of students. Faces are painted, paw print tattoos adhered, and purple beads adorn every neck. The senior section begins frantically waving their hands in the air, screaming “Eighteen! Eighteen!” Like dominoes, the underclassmen sections follow suit.

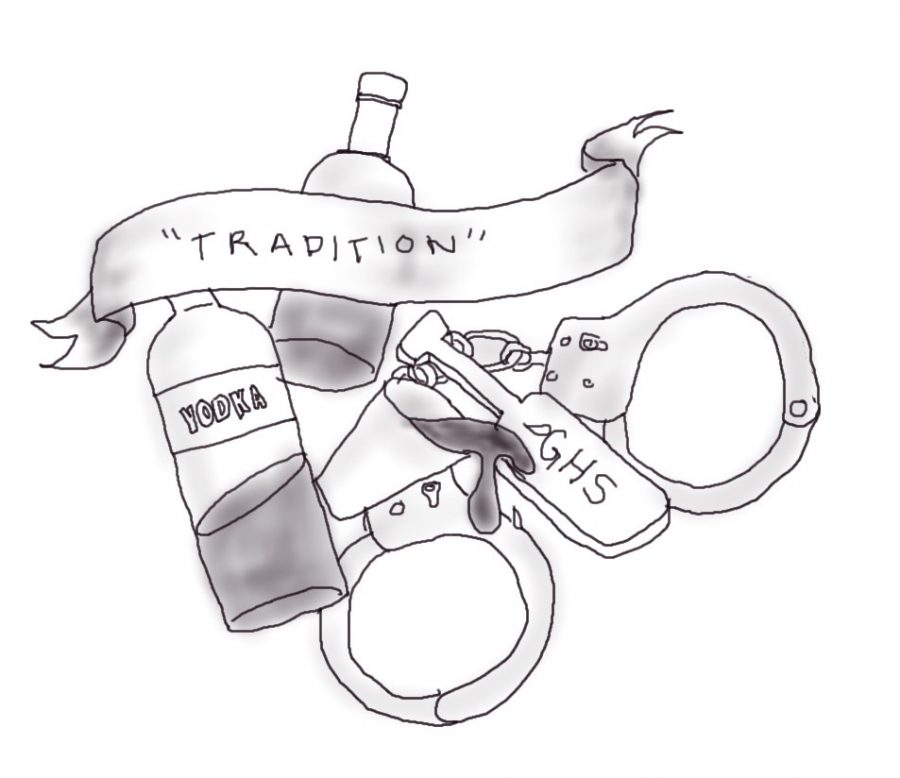

Purple and white day is the embodiment of Garfield’s beloved traditions, which shape our culture and give us pride. Although each school’s traditions vary, the idea of preserving and sentimentalizing certain practices is an essential part of giving any school character. However, Garfield’s romanticized concept of “tradition” has extended beyond the bleachers, and has been used to excuse and rationalize a dangerous party culture. Through repeating this rhetoric, Garfield students have normalized and validated dangerous aspects of our party life, like binge drinking, violent froshing, and hard drug use.

In October 2013, eleven students were suspended from school following one of Garfield’s most public froshing events, with local news publishing scandalous accounts of freshmen being paddled in diapers, forced to drink, and smeared in shoe polish. This was met with an “emergency expulsion” of the students, consistent with Seattle Public Schools guidelines stating that hazing is considered “a criminal offense, and will be treated as such.”

If you search “Garfield froshing” in Google, this incident from 2013 is virtually the only result. However, anyone who has been at Garfield knows that there have been many more since then. Why have Garfield’s extreme froshing incidents been losing attention? The answer lies in the gradual normalization of such dangerous practices in the ongoing evolution of Garfield’s party culture.

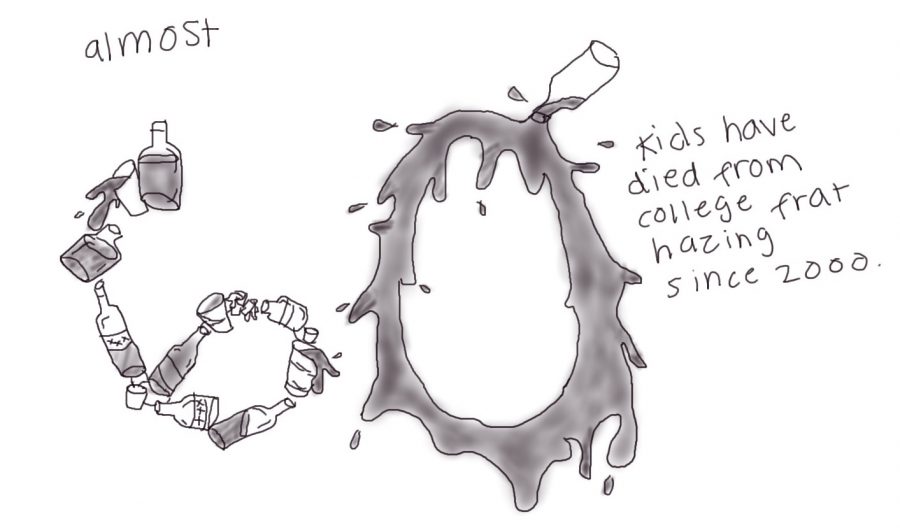

Arguably one of the most unique aspects of Garfield’s party culture is the practice of froshing. Although hazing itself is not specific to Garfield, our school seems to stand alone in managing to have created something that closely mimics college fraternity hazing, which has killed nearly 60 kids since 2000, according to professor of journalism Hank Nuwer. While other high schools do participate in hazing to some degree, Garfield’s relationship with alcohol has taken high school froshing to a whole new level.

Arguably one of the most unique aspects of Garfield’s party culture is the practice of froshing. Although hazing itself is not specific to Garfield, our school seems to stand alone in managing to have created something that closely mimics college fraternity hazing, which has killed nearly 60 kids since 2000, according to professor of journalism Hank Nuwer. While other high schools do participate in hazing to some degree, Garfield’s relationship with alcohol has taken high school froshing to a whole new level.

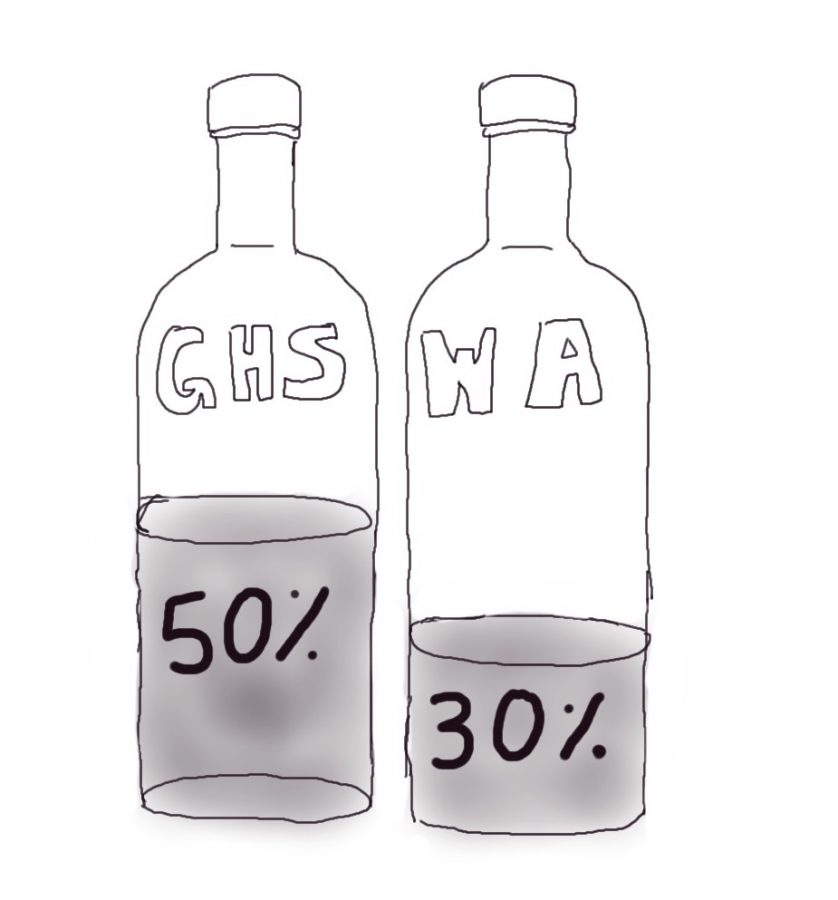

With incidents leading to students being left vomiting at the side of the road or unconscious in a hospital bed, it is clear that heavy drinking is the main factor that sets Garfield’s froshing apart from other schools. So is bulldog drinking a bigger issue than we think? The statistics say yes – Garfield’s drug and alcohol consumption rates are dangerously higher than the Washington state average, according to the 2016 Healthy Youth Survey data. While 32% of 12th graders in Washington state reported drinking alcohol in the past 30 days, nearly half of Garfield seniors reported drinking within this time frame. Garfield students are drinking a whopping 20% more than our peers in the rest of Washington. And this isn’t just kicking back with a Coors Light – over a quarter of Garfield seniors reported heavy binge drinking (5 or more drinks in a small period of time) in the past 2 weeks (that’s right, just 2 weeks).

So what has allowed Garfield’s alcohol-centric party culture to reach such extremes? Normalization. Senior John Smith (name changed to respect anonymity) says it all starts when freshmen enter Garfield, where alcohol is presented as a good thing. “Garfield is so open about alcohol and drugs from the get-go,” Smith says, reflecting on his experiences as both a frosher and a froshee. “Drinking is something [the freshmen] see as cool.” When alcohol and drugs are presented to freshmen in such a casual context, it is then standardized as a part of Garfield’s party culture. Eventually, students begin to accept binge drinking as the norm. “I think it’s normal, but that’s because it’s all I know,” says Smith.

But can we really de-normalize something so intrinsic to Garfield’s culture? Yes. The normalization of dangerous party practices like heavy drinking, aggressive and degrading froshing, and drug abuse all lead back to a single thread of ongoing rhetoric: tradition. Garfield students have used the concept of “tradition” to preserve and validate froshing for years. Yet the need to use “tradition” to defend froshing implies that we all know there is something terribly wrong with what we’re doing in the first place. Smith perfectly embodies this dilemma of Garfield students, saying, “I feel like it’s a tradition, and all traditions are important. But I feel like it’s crazy and it’s dumb.” This thought process is what we should all take a moment to follow, as it is the first step in the process of de-normalizing and invalidating the principles of our self-destructive party culture. Let’s recognize that this rhetoric about “tradition” is bull. Let’s recognize that if we need to make up excuses, then we are doing something very wrong. Let’s recognize that we have normalized a criminal offense. Let’s grow up.