No Child Left Behind

Meany Middle School reopens after eight years.

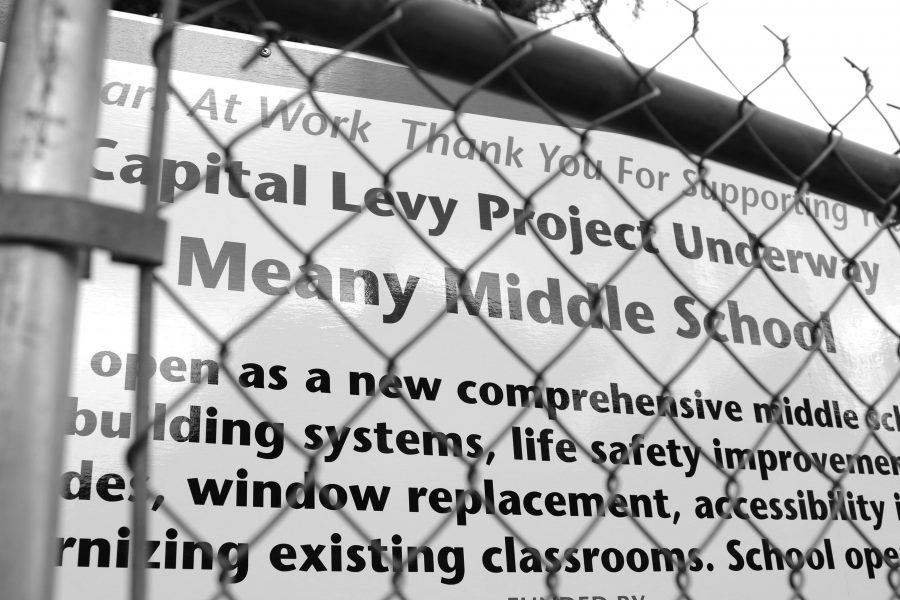

Edmond S. Meany Middle School, which closed in 2009 to make way for Nova Alternative High School and the world school program, will be reopening in the September of 2017.

Their incoming faculty are working hard to combat claims of reduced racial pluralism within their student body. This is due to rising 6th and 7th grade Scholars (formerly known as general education students) who live in Capitol Hill that will be transferred from Washington Middle School to Meany.

“One of the things that is important to me is a term called Honors For All,” says Chanda Oatis, Meany’s incoming principal, referencing a program that has already had a prominent impact on Garfield. “I want all students to have access to every opportunity. If it’s something they can handle, it should be in the classroom for them, not just for students in a separate track.”

Despite the backlash this transfer has received from parents concerned about the lack of racial and cultural diversity in the school, many teachers are looking at the benefits associated with it. “The decrease in Washington’s [Middle School] student body will definitely be a positive,” said Susan Huntley, the tutoring coordinator at Washington Middle School. “The individualized attention that we will be able to provide, we will really be able to get to know students and see what their opportunities are.”

Parents are also growing to like the idea of a new beginning for their students. “Families have been very curious and ask a lot of questions, like what courses will be offered, or about the staff. But as their questions are being answered, there seems to be a growing level of excitement around creating a new school,” says Washington Middle School and former Meany Middle School teacher Robert Rose-Leigh.

Regardless of high hopes and plans for the future, the reopening of Meany as well as the transfer of students from Washington will undoubtedly make changes within Washington Middle School, and the community at large. Friend groups will be broken up, teachers will leave classrooms, and perhaps the factor that has received the greatest amount of criticism is the presumed prioritization of higher education, white students.

“The parents of HCC [Highly Capable Cohort, previously APP] students are often the ones with the loudest voices, are often the ones who volunteer the most and are often the ones who have the biggest pockets. And money talks,” says Huntley.

Although Meany is a comprehensive school, a school that does not select its intake on the basis of academic achievement, Scholars from Washington who live in Meany’s area will not have an option to stay at their current middle school. This can affect families who want their students in higher education program.

Despite this education zoning, Meany’s staff are working to promote pluralism within the school. While Meany was still open, Rose-Leigh expresses how the middle school was incredibly diverse and hopes that the re-opening of the school will be just as much if not more demographically spread.

“It was approximately 55% African American, 15% Latino, 15% Asian/Pacific Islander, 15% White. It was a wonderfully diverse student body, and I had an excellent experience there with students and staff,” he says.

These new features, programs and plans, although ambitious, are being worked on and constantly developed by the faculty at Meany who are dedicated to creating a diverse educational experience for their students. They, along with faculty at other middle schools like Washington are attempting to combat the manifestations of institutionalized racism within the education system.

Photo by Toby Tran